Renal review, just like the internet, a series of tubes

The kidney. The underappreciated organ - because frankly, who wants to talk about the thing that makes urine all day every day? Except when it starts to fail, and then everybody starts panicking. They suddenly remember that it does a lot more than just produce urine. Blood pressure goes wild, anemia develops, the heart flips out, and more. It’s never a good thing for the patient. Chronic kidney disease(CKD) is one of the top 10 leading causes of death in the United States and unfortunately it is something we didn’t have great treatments for until fairly recently. Even then, our treatments are more about preserving what function is left. Ask your friendly nephrologist and they’ll regale you with tales of failed kidney disease trials. But now, whether it is SGLT2i, MRA or ARBs, we have drugs that can help in significant ways.

Perhaps the most unexpected class of kidney drugs was GLP-1 agonists. They’re now considered a pillar of care for CKD because of their beneficial renal effects. But this leads to the obvious question, how is a diabetic/obesity medication helping the kidneys? The answer is multi-factorial with a healthy dollop of it just works and we’re trying to figure it out still shrug emoji. This is my longest and deepest dive yet because, while I’m going to focus on GLP-1 as it relates to the kidneys, I’m also going to be discussing the effects of GIP and glucagon - two hormones where even though we know even LESS about their effects on the kidneys, we at least have enough information to make well-educated hypothetical guesses.

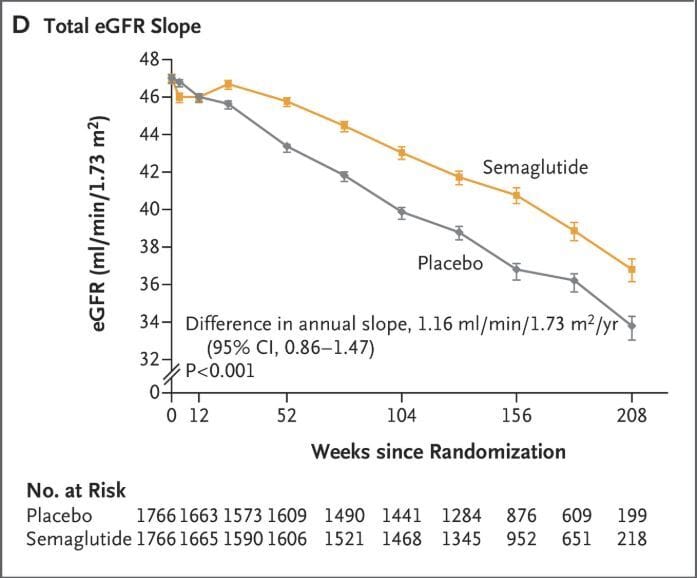

This is actually a hot research topic at the moment right now, too. Novo Nordisk has done the FLOW trial, which was the first to unequivocally show renal benefits.

Decreased GFR slope, showing one of the many benefits of semaglutide in chronic kidney disease

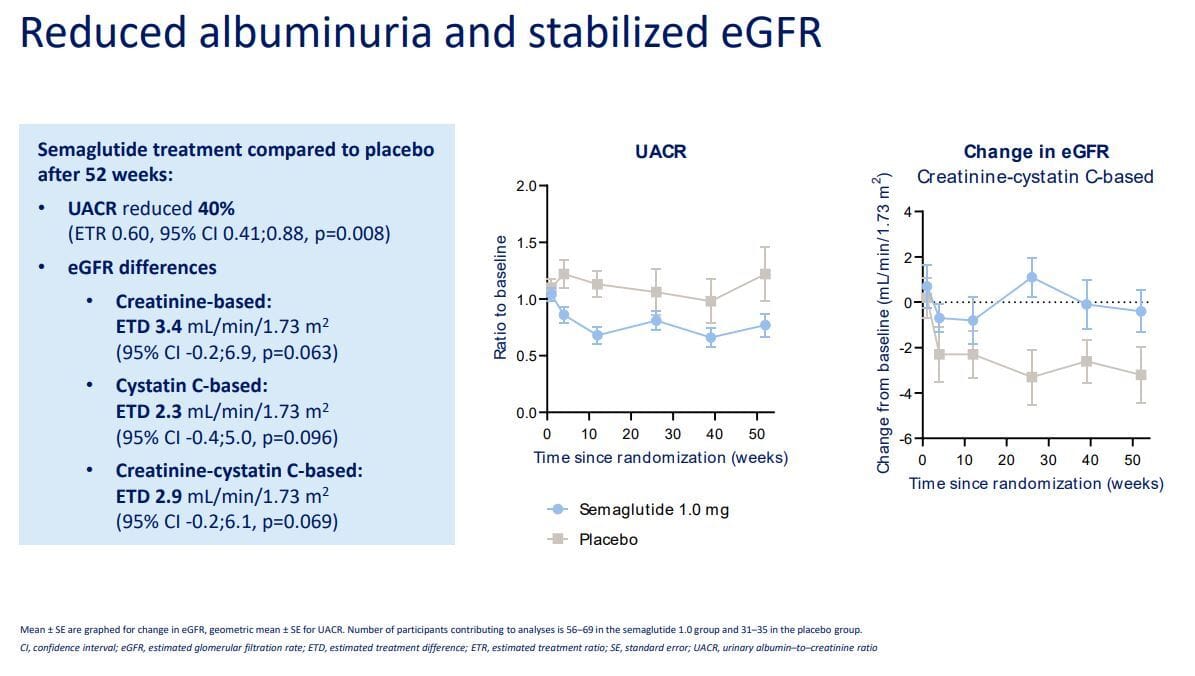

I briefly highlighted the SURPASS-CVOT renal benefits in a prior blog post GIP: SURPASSing all expectations.

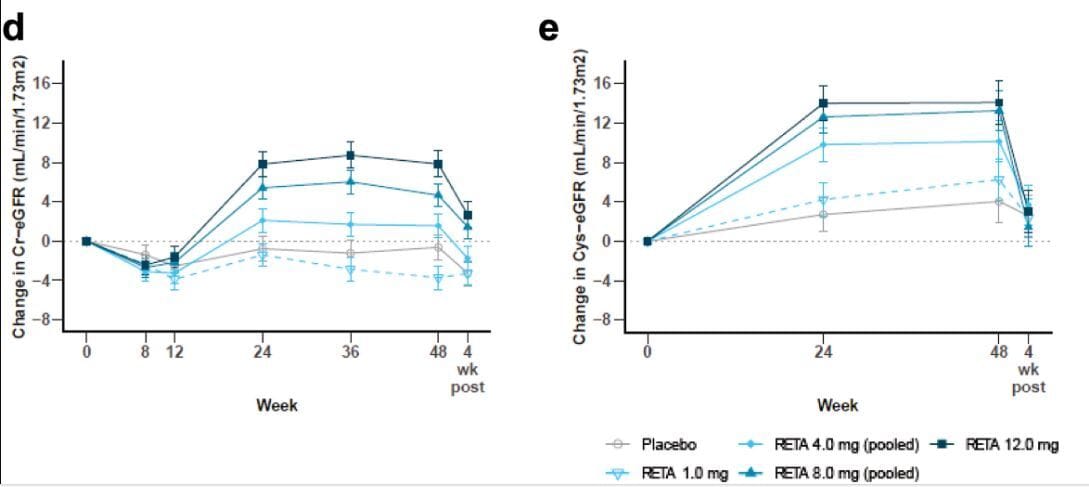

Even better GFR slope changes with tirzepatide

Novo just presented data on a trial called REMODEL, which we’ll discuss along the way, and Lilly has TREASURE-CKD and TRANSCEND-CKD for tirzepatide and retatrutide respectively. In fact, the phase 2 retatrutide GFR slope data is one reason for this article because it suggests a rise in GFR that appears drug mediated:

GFR went UP in phase 2 retatrutide data, and decreased once the drug was stopped, suggesting a drug mediated effect

Boehringer Ingelheim has a CKD trial running for their dual agonist survodutide. Everyone is trying collectively to see how these drugs interact with the kidneys.

With that being said, let’s focus on the easy to explain reasons why GLP-1 medications help the kidneys and slowly get into the more complex reasons, along with some of the (many?) questions still to be answered.

Tubes, tufts and filtration

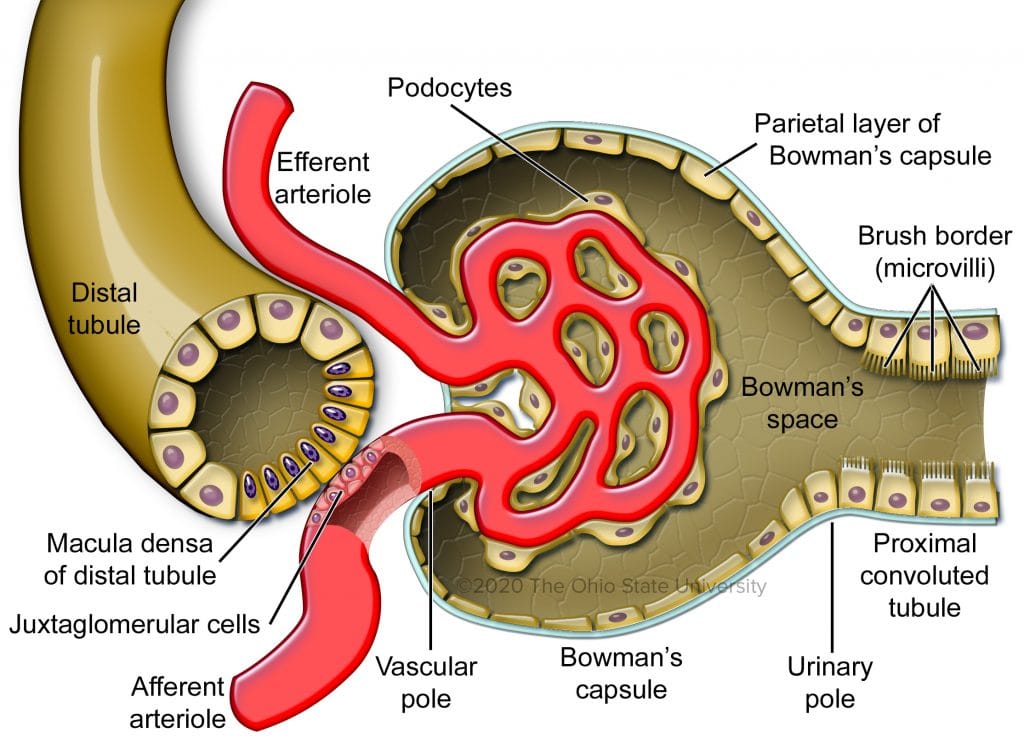

Before we get into this, I feel that it's important to provide a high-level overview of the kidneys itself. Within the kidneys, the structures we care about are located in the nephrons, microscopic functional units that have a series of convoluted and looping (literally) tubes terminating in a glomerulus, a tuft of capillaries where blood filtration occurs. Inside the glomerulus and along these tubes is where the magic of kidney function happens, including filtration of blood at the glomerulus and the regulated reabsorption and secretion of electrolytes and waste products that result in urine production.

This image really captures how tiny and delicate a glomerulus is

The kidneys also broadly help control our systemic blood pressure through a series of hormonal interactions and interplay between multiple organ systems. This system is called the RAAS, or renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. I’ll mostly let the pictures do the talking, but I’ll also include links to some educational videos for those reading who aren’t well versed on how kidneys filter blood:

I’ll also include some very basic definitions here:

Glomerulus: Network of small blood vessels (capillaries) known as a tuft, located at the beginning of a nephron in the kidney. Blood is filtered across the capillary walls through the glomerular filtration barrier, which yields its filtrate of water and soluble substances.

Efferent arteriole: A blood vessel that carries filtered blood away from the glomerulus in the kidney's nephron.

Afferent arteriole: A blood vessel that carries unfiltered blood towards the glomerulus in the kidney's nephron.

Macula Densa: A group of specialized, densely packed cells in the wall of the kidney's distal convoluted tubule that lie adjacent to the afferent arteriole at the glomerulus. These cells act as sensors, monitoring the sodium chloride concentration in the tubular fluid and playing a crucial role in regulating glomerular filtration rate and blood pressure through a process called the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism.

Tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF): A kidney mechanism that regulates the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) by sensing the concentration of sodium chloride in the tubular fluid and signaling the glomerulus to adjust blood flow. When the GFR is too high OR more sodium chloride is delivered to the macula densa cells, it will then constrict the afferent arteriole, reducing the GFR to match the nephron's capacity for reabsorption. When the GFR or sodium chloride flow is low, the opposite occurs, and the macula densa signals for vasodilation, increasing the GFR.

Glomerular filtration rate: Flow rate at which blood is filtered by the kidneys to form urine. It is a key measure of kidney function, indicating how much blood passes through the tiny filters in the kidneys (glomeruli) each minute. A ‘healthy’ GFR is typically 90–120 mL/min.

Less pressure, less protein for happy beans

The current generation of GLP-1 medications all lower blood pressure to some extent. Semaglutide does it, tirzepatide does it. Next generation medications like orforglipron and retatrutide also do it. All of them lower it to varying degrees. We’ll explore the why later on, but in simple terms, lower blood pressure leads to better kidney outcomes. Inside each of your kidneys are somewhere between 500,000 to 1 million glomeruli and these little filters are highly sensitive to pressure changes. Consistently higher pressures slowly damage these delicate structures, and simply lowering the pressure can relieve this stress on the kidney and preserve function over the long term.

When these filters are damaged or stressed, they can also leak small amounts of protein, specifically microalbumin, into your urine - and that is the next area where GLP-1 medications can help. In what is again a class effect, GLP-1 medications reduce microalbuminuria to varying degrees. This is again most likely related to changes in blood pressure, alterations in RAAS signaling and possibly inflammation, and reducing strain on the filtering system (which keeps microalbumin in circulation where it belongs).

Finally, and perhaps also obviously, for patients with diabetes, the glucose lowering effect of GLP-1 medications reduces the strain on the kidneys. Glucose itself is damaging to the kidney in ways we’ll discuss.

GLP-1, GIP, Glucagon Receptors, Receptors Everywhere?

I sincerely hope you enjoyed the easy part of this post, because now it gets complicated. In this next section, I want to dive into where GLP-1, GIP and Glucagon are expressed in the kidney, and then explore what they’re actually doing there. Things will get messy, so I’m including as many graphics as I can. Let’s start with GIP receptors in the kidney:

Oh, well, that’s awkward.

What about around the kidney? Well, probably yes. There are probably GIP receptors in the adipocytes surrounding the kidney, and possibly in the arterial walls entering the kidneys since the GIP receptor is found on vascular endothelial cells (VECs) in blood vessels. As I’ve discussed before, GIP agonism within adipocytes would help to slowly reduce the size of adipocytes while also reducing inflammatory biomarkers as well. This would indirectly help the kidney with a reduction in local inflammation. We have some evidence that VECs help the body and, by extension, the kidney. Specifically, GIP can stimulate the production of nitric oxide in certain blood vessels. Nitric oxide is a potent vasodilator leading to decreased blood pressure and decreased inflammation in the blood vessel wall. Both of these effects would be beneficial to the kidney for the reasons already discussed. With that, there isn’t much more to add about GIP; let’s get to the receptors that are expressed in the kidney.

GLP-1 is the most studied of these three receptor classes, and it is the one we understand best. With the recent completion of the REMODEL trial, we now have an even clearer picture, so let’s get into it.

Mechanisms related to GLP-1’s renal benefits

Less albuminuria, better GFR

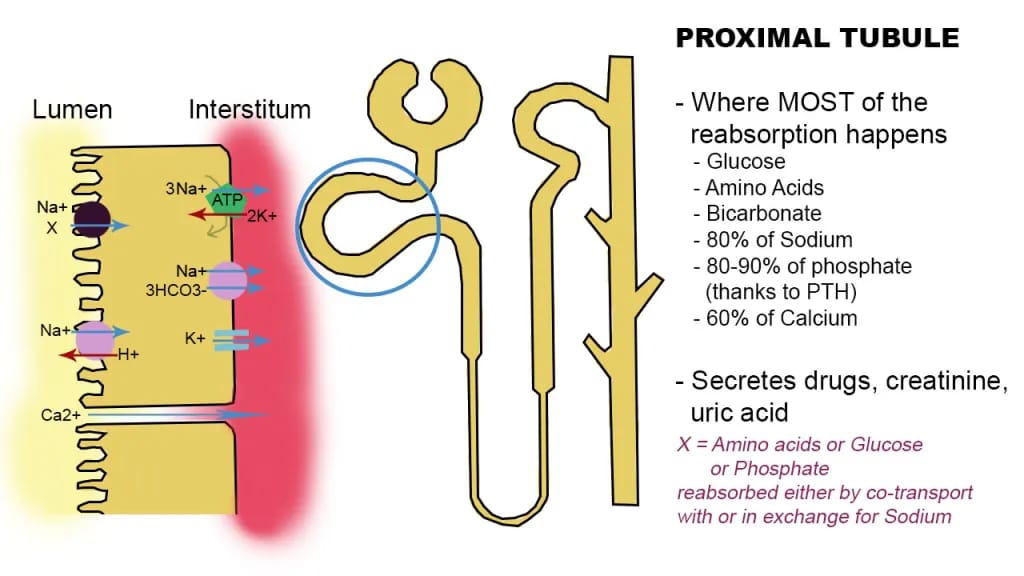

As of the time of writing there are two major regions of the kidney where the GLP-1 receptor seems to be expressed. The first is the proximal tubule, where GLP-1 agonism can induce natriuresis (increased sodium excretion) and diuresis (increased water excretion). This effect is thought to be partly mediated by inhibiting the activity of the Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 in the proximal tubule of the nephron, reducing sodium reabsorption and promoting its excretion along with water. As the saying goes in medicine, where salt goes, water follows.

GLP-1 receptors are also found in renal arterioles, especially in cells that also produce renin known as juxtaglomerular cells. Here, it seems that GLP-1 agonism reduces the circulating levels of angiotensin II, a potent vasoconstrictor.

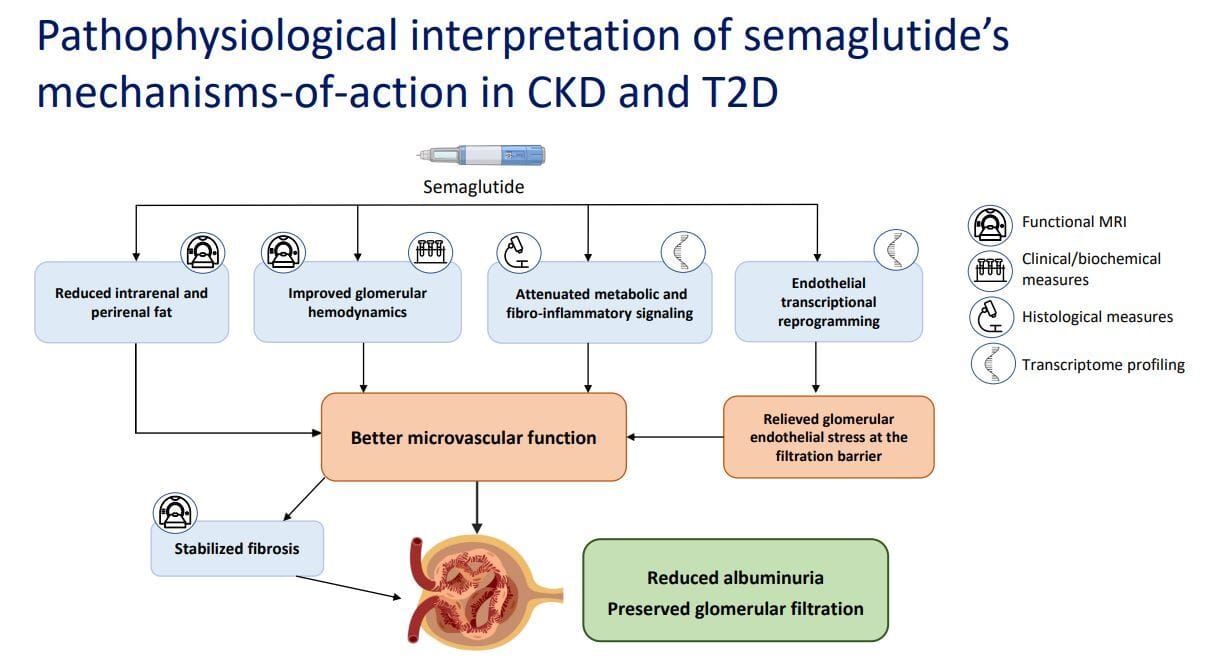

GLP-1 agonists also act in an anti-inflammatory manner. As seen in the images, GLP-1 agonism reduces inflammatory signaling, stabilizes renal fibrosis, decreases peri- and intrarenal fat, and downregulates stress and inflammatory genes. In addition, other studies have shown that GLP-1 receptor agonists reduce systemic inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein, interleukin-1B, interleukin-6, and Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-a), all of which can be damaging to the kidney.

Finally, they also consistently reduce albuminuria, the presence of albumin in the urine, likely due to a combination of the above factors that improve microvascular function, reduce stress on the glomeruli and podocytes, the filtration units, and ultimately preserve filtration. This can be seen especially well with three measures that REMODEL looked at: creatinine clearance, filtration fraction, and renal artery resistance index.

In simple terms, there was lower renal artery resistance, meaning lower intrarenal pressure, along with an increased filtration fraction and creatinine clearance, reflecting better filtration and fluid clearance. Put another way, lower pressure within the kidney actually allows more efficient filtration of fluid. Think of a garden hose turned on to full blast. If you partially cover the end with your finger, you increase pressure but decrease flow. Remove your finger, and flow increases while pressure drops. Now imagine the impact of increased pressure on the tiny delicate glomeruli and you can understand why lowering pressure preserves those filters.

I have to move on from GLP-1 as there are even more factors at play that deserve their own sections. Let's switch gears to glucagon.

If you’ve read my first two posts I ever made on this blog,

you’ll know that glucagon has been misunderstood, misrepresented, and frankly poorly researched - even more so in the kidney. Most of the data on what glucagon does in the kidney is over 20 years old and in some cases over 50 years old! When I say that we have known that glucagon infusions cause an increase in GFR and modify excretion of electrolytes, that knowledge comes from scientific articles published in the 1950s & 1960s!!

1958 study showing glucagon infusions in men increased GFR!

1977 study, again with a rise in GFR rise in filtration fraction and brief rise in renal plasma flow

Fortunately, research on glucagon has picked up in the last decade and even more recently with the development of glucagon agonists. So again, let’s review what we know:

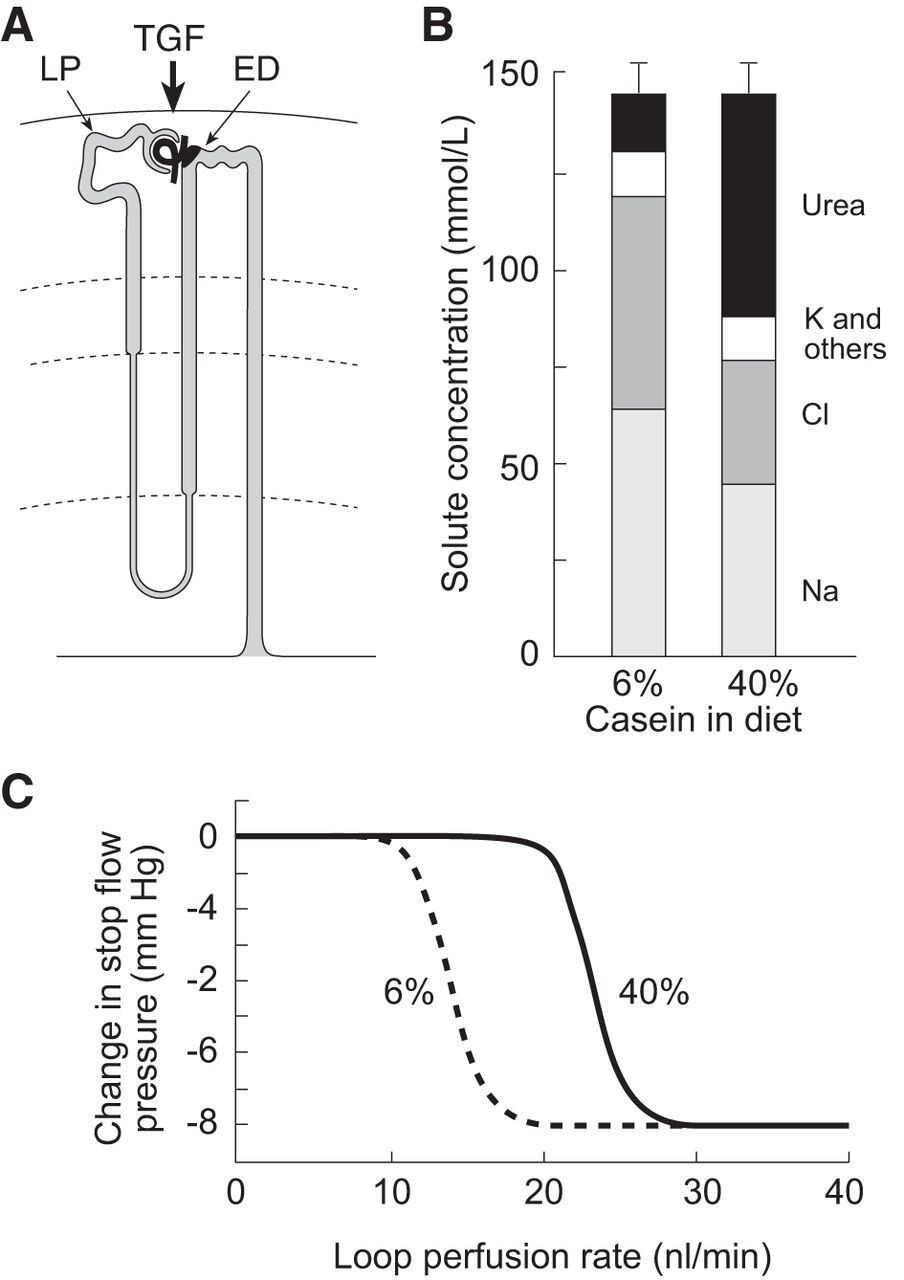

Glucagon receptors are expressed in multiple places in the nephron, including the thick ascending limb, distal convoluted tubule (including the macula densa), and the collecting duct. The macula densa is critical to the tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF) which regulates fluid flow through the afferent arteriole and can raise or lower GFR depending on conditions. Video on it here:

In a picture, salt is the driver of the TGF and ultimately GFR

Glucagon modulates transport of electrolytes like sodium, potassium, chloride, calcium, and phosphate along the nephron segments listed. In particular, changes in sodium reabsorption in the thick ascending limb alter the amount of sodium sensed by the macula densa, which appears to account for some of the observed changes in GFR.

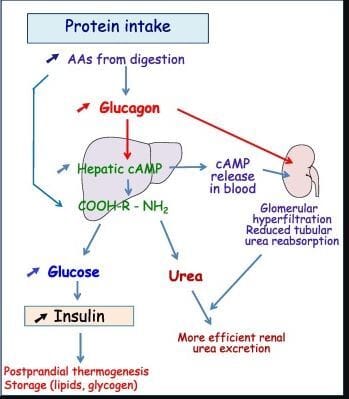

Glucagon promotes the amino acid catabolism (breakdown) in the liver, increasing hepatic cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) production and urea synthesis. Because the body cannot store nitrogenous waste such as urea, the excess must be excreted by the kidneys. This hepatorenal axis helps maintain nitrogen balance, especially after a high-protein meal. Indeed, high protein intake, or ingestion of particular amino acids, has been shown to increase GFR in human and animal models. One leading hypothesis is that this response evolved to rapidly eliminate toxic by-products of protein catabolism, including urea, ammonia, and uric acid. In contrast, carbohydrate metabolism primarily produces water and CO2, which are easily removed by the lungs and kidneys.

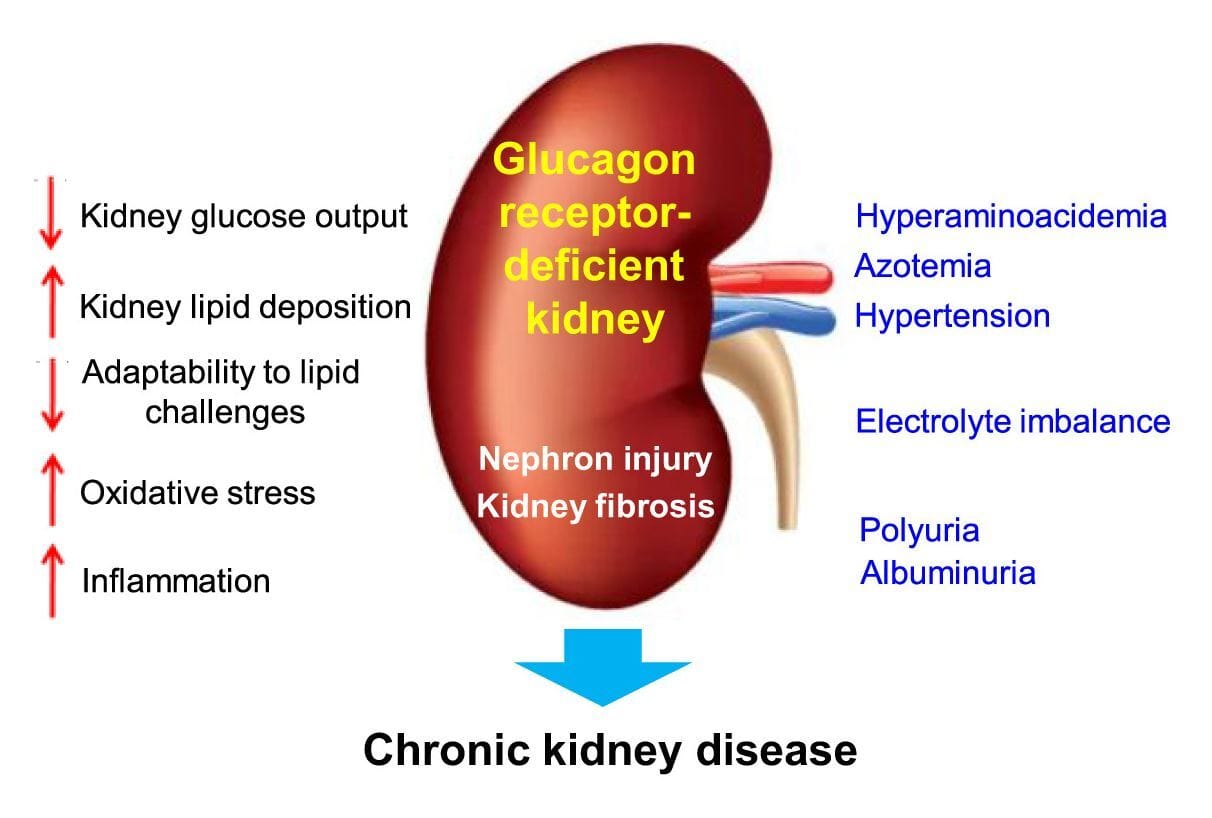

Studies in animals show that a lack of kidney glucagon signaling leads to metabolic dysregulation, including increased oxidative stress, hypertension, higher levels of inflammation, excess lipid accumulation in the liver and kidney, and eventually fibrosis (scarring) in the kidney. All of these are seen in chronic kidney and diabetic kidney disease. Glucagon therefore is critical to maintaining healthy kidneys.

I’ll pause here with glucagon just as I did with GLP-1, since there’s a deeper layer of mechanisms involved and some of these effects likely overlap or are synergistic.

Peeling away the onion: sodium, vasopressin, urea, cAMP & ketones

I want to circle back to sodium in the context of both GLP-1 and glucagon. GLP-1, as noted before, promotes sodium and water excretion (natriuresis and diuresis, respectively). Reducing both water and sodium through urination will reduce blood pressure, and this action alone is renoprotective. However, if a GLP-1 agonist also has glucagon activity, you’re now altering that sodium flux even more. Glucagon will further increase the excretion of sodium and water, and importantly urea. Viewed outside a pharmacological framework, this makes sense; because glucagon facilitates removal of nitrogenous waste. The problem is that increasing water loss through both GLP-1 and glucagon raises the risk of excessive fluid loss and potential dehydration.

Enter the glucagon-vasopressin-urea pathway (GUVP).

Expression of Glucagon and Vasopressin along the nephron

The lay summary of this pathway is as follows: it is a system involving the liver, kidneys and technically the brain that promotes excretion of nitrogenous waste such as urea while conserving water. This system tends to be most active following a protein-rich meal, which stimulates glucagon secretion from the pancreas:

The more technical breakdown is as follows and it’s important to know how a glucagon agonist may be beneficial to the kidney. Ingestion of a protein meal directly stimulates the secretion of glucagon from pancreatic alpha cells. In this context, a glucagon agonist effectively mimics that signal by activating the same pathway. As my blog on glucagon agonism discusses, glucagon does far more than regulate glucose and insulin. It acts as a broad regulatory hormone and, in this setting, promotes ureagenesis and the disposal of nitrogenous waste. At the same time, protein intake or glucagon agonism increase the secretion of vasopressin, or anti-diuretic hormone. Vasopressin's classical role is (no surprise!) water conservation. You might see where this is heading.

GVUP in an image

High protein diet shows an increase in urea excretion, with a decreased amount of Na and Cl which drives the TGF to increase GFR as the MD senses less Na

Now let’s see how they both work in the kidney. First, glucagon (as discussed) increases GFR at least in part through the macula densa. This, in turn, increases flow through the glomerulus and delivers more urea, water and solutes for filtration. Both hormones are highly expressed in the thick ascending limb, where sodium and chloride reabsorption is increased (most likely by both hormones) into the inner medullary space. As we move further along the nephron, we reach the inner medullary collecting duct where vasopressin exerts its most important effects on water conservation. Here it binds to V2 receptors which increase the expression and activation of UT-A1, the urea transporter A1. This increases the permeability of the collecting duct, allowing some urea to rapidly diffuse into the inner medullary interstitium, the same space containing sodium and chloride. Urea then enters a recycling process that raises interstitial osmolarity, creating a driving force for water reabsorption along the collecting duct. This conserves water while further concentrating the urine for final excretion. The result is water conservation with further concentration of the urine, allowing excess urea to be eliminated without excessive water loss.

Now, any nephrologist worth his salt will tell you that glomerular hyperfiltration is bad and therefore this increase in GFR caused by the GVUP will eventually lead to problems. However, remember that GLP-1 has a renoprotective effect in the glomeruli, podocytes, and proximal tubule.

Not to add another layer, but we can’t discuss this rise in GFR without mentioning yet another component that appears to be critical for the GVUP pathway to function: cyclic adenosine monophosphate, or cAMP. cAMP is what is called a "second messenger" and within cells, it relays signals from hormones and neurotransmitters to trigger internal responses like metabolism and gene changes. In this context, it assists both glucagon and vasopressin. Glucagon agonism induces an excessive amount of hepatically formed cAMP into the bloodstream, which travels to the kidney. In an older paper from 1996(!) researchers investigated what drives the increase in GFR with glucagon and found that high doses of glucagon plus cAMP were required. Infusions of cAMP alone or urea showed a mild trend towards increased GFR, but supraphysiological doses of glucagon or low doses of glucagon combined with cAMP and urea (simulating a high protein intake) reliably and consistently increased GFR. Therefore, it seems that the combination of liver-derived cAMP and the action of glucagon in the kidney is necessary to increase GFR.

I have mentioned the macula densa multiple times as a key factor in both the rise in GFR and changes in tubuloglomerular feedback. But I haven’t yet explained its role or how the GVUP pathway actively helps the kidney.

What is the Macula Densa? It’s a highly specialized cluster of about 25 cells that abuts the afferent arteriole as it enters the glomerulus.

Macula densa overlaying the afferent arteriole

Technically, it is also part of the distal convoluted tubule but, as noted, the cells are differentiated from the surrounding tubular cells. These cells help control TGF which then can directly act upon GFR. If fluid flow is high, more sodium chloride reaches the MD which then constricts the afferent arteriole and reduces GFR. But, if the flow of fluid or the concentration of sodium chloride are low, the opposite happens: the MD releases vasodilators and GFR rises. As we just discussed, glucagon leads to more reabsorption of sodium chloride prior to reaching the MD. It then senses this as low GFR and dilates the afferent arteriole in response. This increases GFR in an attempt to futilely compensate. However, recent research shows the macula densa isn’t just a salt sensor but also a repair mechanism, one that glucagon agonism might trigger as a byproduct.

This next section is a highly speculative hypothesis on my part, but it could represent a major breakthrough in the treatment of chronic kidney disease. A 2024 study showed that macula densa cells exhibit neuronal differentiation, meaning that these cells could regulate repair and remodeling of the glomerulus itself. The MD was found to control resident progenitor cells and direct them to differentiate, forming new tissue and remodeling certain kidney structures. More specifically, the protein CCN1 was identified and expressed in human MD cells, but was reduced in CKD, with the authors noting that low CCN1 levels seemed to be associated with reduced GFR. CCN1 is a Swiss army knife of a protein that can promote growth and angiogenesis, induce apoptosis, and help clear or prevent fibrosis, among other roles.

MD cells signaling CCN1 to precursor cells to repair and differentiate

With that in mind, the authors of this study deliberately induced glomerulosclerosis in a set of rodents and then treated them with CCN1 or MD cells exposed to a persistent low salt state. Both groups saw a reduction in albuminuria, but the authors observed an increase in GFR and a reversal of glomerulosclerosis and tubular fibrosis in the MD cells that were exposed to a low salt state. Importantly, these rodents were also treated with ACE inhibitors, which introduces a confounder because not all humans are on ACE inhibitors. However, as discussed earlier, GLP-1 can block angiotensin II, which may help augment this renal repair mechanism. ACE inhibitors also block angiotensin II.

The dual model hypothesis of the MD, GFR control and repair

All of that leads to my speculative hypothesis for why dual and triple GLP-1 and glucagon agonists appear to increase GFR while remaining renoprotective. Glucagon agonism may mimic the low salt signaling observed in this study, thereby raising GFR and activating macula densa repair signaling, including CCN1. At the same time, GLP-1 agonism blocks angiotensin II and alters the RAAS. Together, these combined actions may allow the kidney to repair itself, reduce albuminuria, and increase GFR.

Essentially, macula densa cells are the key sensory and regulatory cell type that monitors the kidney’s health and, during periods of stress such as salt loss, fluid loss, or injury, seem to mobilize an inherent capacity for self-repair.

Ketones are good…for the kidney?

Let’s start this section with more renal biology! This section focuses on the proximal tubules, which sit immediately adjacent to the glomeruli and do most of the heavy lifting for reabsorption, including glucose, salts, water, amino acids and more. Some of this occurs by passive diffusion, but a substantial portion requires active transport. Because of this high workload, the cells in the proximal tubules consume large amounts of energy.

Proximal tubule with active transporters noted

They rely primarily on fatty acid oxidation (FAO) to produce ATP and only have a limited capacity for glycolysis. This is necessary because active transport of such large solute loads is energy intensive. Fatty acid oxidation yields approximately 106 to 129 ATP per molecule, whereas glycolysis produces only about 30 to 32 ATP.

Unfortunately, when the kidney is injured or damaged from hypertension, diabetes, or other causes, the proximal tubules will shift to glycolysis for energy and downregulate FAO. This transition further exacerbates kidney disease symptoms, as these cells lose more than 70 percent of their energy producing capacity.

Enter ketone bodies, which can serve as an alternative energy source when FAO is impaired. Renal proximal tubules can uptake ketone bodies and, through ketolysis, generate 2 molecules of acetyl-CoA which can then enter the Krebs cycle to produce about 20 ATP. This can provide extra energy for already stressed or damaged kidneys. There is also evidence that ketone utilization may help proximal tubules restart fatty acid oxidation, leading to improved function. But wait, there’s more!

Ketone bodies, specifically beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB), have a few other tricks up their fruity-smelling sleeves. First, they can activate Nrf2, one of our body’s regulators of antioxidant responses. Its activation can upregulate antioxidant genes that can help clear reactive oxygen species. (Oxidative stress is a major contributor to kidney damage and fibrosis.) Next, BHB can suppress two particular pathways, mTORC1 & NLRP3 inflammasome (what an obvious name!) that both cause inflammation, promote pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1B or IL-18, and in general push the body toward self damage.

SGLT2i can also inhibit mTORC1 through increased ketones, helping slow damage

In the case of the kidney, both of these pathways can induce fibrosis, tissue damage, and cell death. Finally, BHB can also have an effect on renal fibrosis in yet another manner, this time through TGF-beta (Transforming Growth Factor-beta), one of the primary drivers of kidney fibrosis. Low levels of ketosis can reduce the activation of this harmful factor.

But how does GLP-1/GIP/glucagon play into all of this? Only one of those incretins can reliably induce ketosis: glucagon.

Glucagon agonism can reliably induce ketosis at a high enough dose. Retatrutide and Mazdutide, both Eli Lilly drugs, have data showing an increase in BHB. Add this to the list of potential kidney benefits of drugs with glucagon agonism.

Phase 2 retatrutide data showing the increase in BHB at 24 and 48 weeks

Supplying additional fuel to the kidney could support the repair mechanisms discussed above. This is speculative, but the potential synergy is plausible.

RAGEing along with ceramides, and the vicious cycle of inflammation

This last section covers two higher level topics that get little attention but are well-known contributors to kidney damage. Both can be countered by GLP-1/GIP/Glucagon. The first involves ceramides. If you have heard of them at all, it is likely through skin care, where said compounds help maintain skin integrity and act as the mortar between cells in the outer layers. Internally, however, ceramides can be highly damaging to multiple organ systems, including the kidneys.

Without adding another biology lesson, ceramides are technically a form of lipid with 12 different classes ranging from short chain to long chain. Painting with a broad brush, long chain ceramides are usually found in the skin and less damaging, while short chain and saturated ceramides tend to be highly toxic and proinflammatory.

In the kidney, ceramides are particularly damaging to the glomeruli and proximal tubules. They injure podocytes and proximal tubule cells, trigger apoptosis (cell death), and promote the accumulation of mitochondria that produce less energy. As we just discussed, reduced energy production in proximal tubule cells drives further kidney damage, fibrosis, and disease progression. Ceramides can also increase the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to further cell damage and activation of inflammatory signalling cascades.

Reader's Digest version: Short chain ceramides activate pro-death and pro-scarring pathways while impairing the kidney’s energy generating capacity required for normal function. They also contribute to whole body insulin resistance.

In a chart, ceramides causing havoc in the kidney. Note the Serine and Palmitoyl-CoA in the pathway to the left, more on that in a moment.

There is a solution which we’ll get to in a moment, as I must mention the second high-level topic.

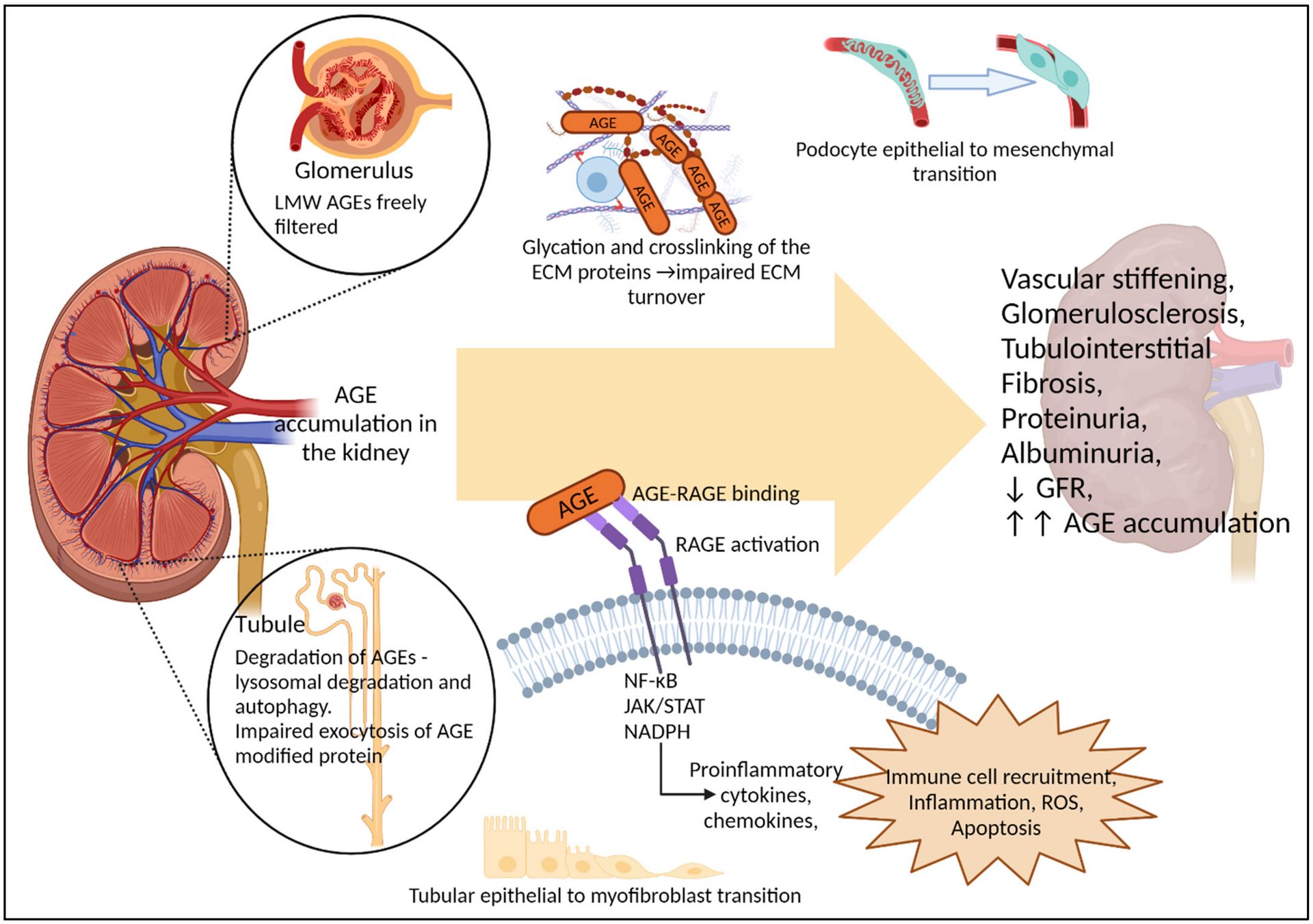

Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) are proteins or lipids that non-enzymatically become glycated after exposure to sugars like glucose and then bind to receptors for advanced glycation end products (RAGEs). They are harmful compounds that form primarily under conditions of high glucose, oxidative stress, metabolic stress, and aging. They accumulate in tissues, driving inflammation, amplifying oxidative stress, and forming complex, damaging structures.

In the kidneys, they accumulate in both the glomeruli and proximal tubules, where they can form cross links with existing collagen proteins. This stiffens and thickens the tissue into what we call glomerulosclerosis. The resulting structural damage allows protein to leak into the urine and can impair blood flow into and out of the glomeruli, reducing overall GFR.

AGEs bound to RAGEs tend to increase oxidative stress, promote kidney fibrosis, and cause further damage. This signaling reduces AGE clearance, increasing the likelihood of collagen cross linking. The resulting inflammation also promotes ceramide accumulation, creating a vicious cycle of renal injury. This process is especially prominent in diabetic nephropathy, where chronic hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia drive excess AGE and ceramide production.

Reader's Digest version: AGEs damage the kidney by physically damaging its filtering structures and by activating pathways (via RAGE) that promote a chronic state of metabolic stress and inflammation, resulting in tissue scarring and eventually chronic kidney disease.

In a chart, all the badness of AGEs

How can incretin hormones help here? For once, I get to mention them all!

Excess glucose drives formation of AGEs, so it seems reasonable that lowering glucose reduces AGE production. You're correct if you guessed that GLP-1 and GIP can help lower blood glucose and directly address the root cause of AGE formation.

In addition, both GLP-1 and GIP agonism reduce inflammation and the inflammatory marker production, lowering the likelihood that AGEs and ceramides trigger this inflammatory cycle.

Ceramides are more complicated and require some speculation. Keep that in mind for the next paragraph or two.

The key factor here is glucagon. To form ceramides, the body needs two compounds: serine, a nonessential amino acid the body can synthesize, and palmitoyl-CoA. This initial step is rate-limited. Glucagon further constrains this reaction through two mechanisms. First, prolonged glucagon agonism has a known catabolic effect on circulating amino acids. It reduces circulating levels of several amino acids, including serine, by roughly 20%, based on phase 2 data from a retatrutide trial in people with diabetes. Second, palmitoyl-CoA is used as a substrate (fuel) for beta-oxidation of fatty acids, and glucagon agonism increases beta oxidation, reducing available palmitoyl-CoA.

Taken together, and this is the speculative part, these effects should suppress ceramide synthesis. Similar effects have been shown with other compounds, but this has not yet been tested with a glucagon agonist.

That covers this topic for now. If you made it this far, all that’s left is a wrap up of my thoughts and a promise that when results from these renal studies become available, I’ll be writing about them.

What we stand to learn in 2026

As I write this in December 2025, the TRANSCEND-CKD trial of retatrutide has just finished, but no data have been published yet. REMODEL just published its findings showing with a GLP-1 mono-agonist can do. We also have data from FLOW and SURPASS-CVOT showing profound renal benefits that slow the progression of GFR decline and reduce mortality. Other CKD Trials involving survodutide and tirzepatide are a year away from completion. I hope I have impressed upon you that GLP-1 itself along with GIP and especially glucagon could have multiple benefits for the kidney. Some of these benefits could truly revolutionize the treatment of chronic kidney disease. The TRANSCEND-CKD trial in particular was enlightening to this article as Eli Lilly is looking at essentially all of these topics I covered today as to the how and why these medications are working. That small phase 2 trial could potentially lead to new discoveries on its own and will certainly influence renal research in the coming years.

Why? Because if the GFR rise with glucagon agonists is real and not due to harmful hyperfiltration, it would be earth-shattering for medicine and nephrology. If that same mechanism also drives the macula dense to help repair the glomeruli, podocytes, basement membrane and proximal tubule, it will again challenge the foundations of nephrology. Even if glucagon agonism doesn't repair the structures but rather increases GFR without damaging glomeruli, that would be critical to millions of patients worldwide. The idea that we could stall the progression of CKD and delay or prevent dialysis and/or kidney transplantation would save countless lives and billions of dollars in health care costs worldwide. It would reduce mortality as well, as we have seen from the FLOW and SURPASS CVOT trials. Put bluntly, the goal is to stall CKD, so patients die from causes other than renal failure.

The impact of these drugs also raises some very serious questions. How do you improve access to these drugs? How do you price a drug that could potentially prevent a patient from requiring dialysis? Are these drugs beneficial in other chronic kidney diseases such as IgA nephropathy, lupus nephritis, interstitial nephritis, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, or kidney stone disease? At what point is it too late to start therapy? Similar questions are being raised in liver disease. GLP-1 therapies can treat fatty liver diseases, steatohepatitis and may even affect cirrhosis, raising the same pricing questions. What happens to kidney function after the drug is stopped? Are the benefits immediately lost, or is there a legacy effect if the kidney is able to repair itself?

I don’t pretend to have answers to any of those questions. However, 2026 is likely to bring a flood of data on the renal benefits of GLP-1 therapies. We will also see renal outcomes data from the first amylin agonist, which has its own kidney interactions that remain poorly understood. Early signals from Lilly’s eloralintide data are potentially promising for renal protection as well.

Stay tuned and thank you for reading this far! This is truly a labor of love on my part. If you see any errors or corrections, please feel free to point them out so I can make revisions.

Next will be a summary of the key clinical trials expected to report data in 2026, along with my brief thoughts on each.

References: